Demographics Watch – A Public Debt Timebomb

Welcome to a new Demographics Watch! We will take a deep dive into public debt and how it’s related to birth rates and ageing population. If you want to go even deeper into our numbers, we have set up a Demographics page on our Datahub, where you can play around with the numbers yourself. It’s for Premium users only – but you can try it out for free with a 14-day trial.

Demographics Watch – A Public Debt Timebomb

In our first Demographics Watch article, we introduced ‘The Problem Index’ – a measure of a country’s ability to deal with an ageing population. Weighing the pull and push forces of growing dependency (an increasing older population relying on its diminishing working age population) and migration (as one potential way to fill this gap), we outlined the countries most vulnerable to a continuation, or worsening of current demographic trends. Unsurprisingly, it didn’t make for comfortable reading anywhere, but the index suggested two major problem regions – Eastern and Southern Europe, and East Asia.

We also highlighted that the Problem Index would serve as the groundwork on which we’d build. Today, we want to expand upon the pure demographic trends explored by considering the second order economic impacts captured by the Problem Index – namely, an ageing population’s impact on a country’s public debt.

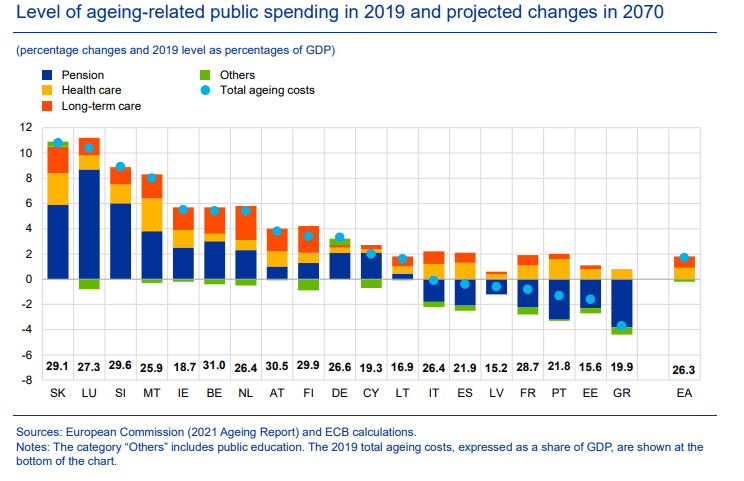

Before we delve into the forecasts and data itself, a brief 101. The theory itself is relatively straightforward: ageing populations – people living longer and the relative size of the labour force shrinking – tend to act as a drain on public resources through the healthcare, social security and pension channels. Simply put, taxes paid into the system begin to dwindle relative to the resources drained out. Let’s be clear: this is a nuanced topic with many moving parts (taxes on growing pension income offsetting some spending, differing levels of saving rates across generations leading to trickle-down effects, shifts in productivity leading to structural changes to name a few), but the evidence and literature illustrate a general trend of increasing public expenditure as populations age. The ECB illustrated it nicely in its 2022 Ageing Report:

Source: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpops/ecb.op296~aaf209ffe5.en.pdf

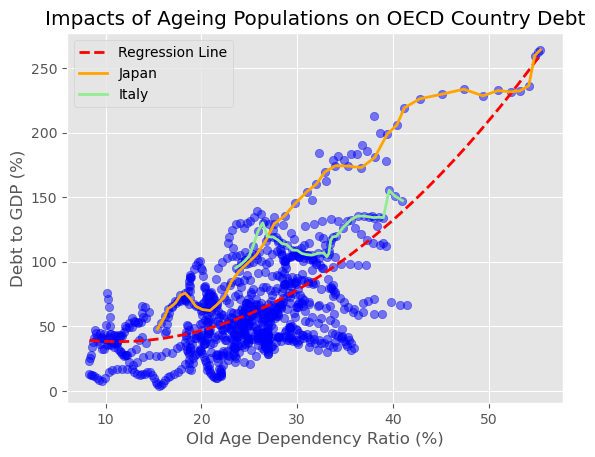

We rely on the ‘debt-to-GDP’ ratio as our comparable measure of public indebtedness, the ratio between a country’s total government debt and its economic output. We often think of this as a proxy for national economic leverage, or how capable a country is of financing its own debt. The higher the ratio, the more debt there is to finance. But disclaimers abound: it doesn’t follow that a ratio in excess of 100% means a country is insolvent. In fact, we’ll find that 1) many countries are already in that exact position, 2) in the absence of more drastic policy or economic changes, the world will likely have to get used to public debt levels well in excess of 100%, if not a few hundred more.

Dependency and Debt

Before looking forward, we need to go back. The below chart plots two features: 1) the Old Age Dependency Ratio – a measure of the economically inactive population aged 65+ relative to the working age population, 2) the Debt to GDP ratio of a country. Building upon historical data over the last 40 years across OECD countries, we observe a key, positive non-linear relationship between dependency and public debt. Per our 101, as a country grows increasingly reliant on its working age population, its capacity to finance its borrowing diminishes.

Within the scatter, the blistering growth of public debt and already-massive dependency dynamic within Japan stands out. For reference, consider Italy – as per our first Problem Index article, only just behind Japan in terms of old age dependency – which, even in its unenviable position, remains echelons away in debt terms. Let’s briefly clarify that Japan indeed remains something of an exception, whose unique position has allowed its situation to manifest as such: it remains the world’s largest creditor nation, its central bank has had almost unlimited reign in utilising quantitative easing of some form, and its debt is largely domestically-owned. But the point we hope to hammer home here is that painting Japan as an exception misses the mark – it isn’t necessarily about the absolute level of debt, but the impact on the trajectory that an ageing population has, irrespective of starting point. The cases of Japan and Italy (amongst many others in the OECD) paint the same picture of growing dependency leading to further borrowing albeit from different levels due to structural, country-specific reasons.

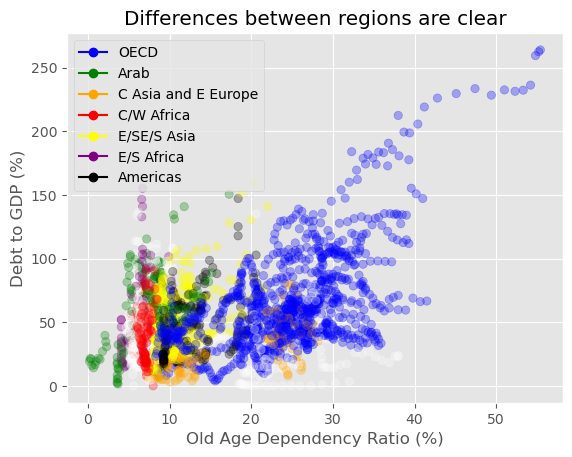

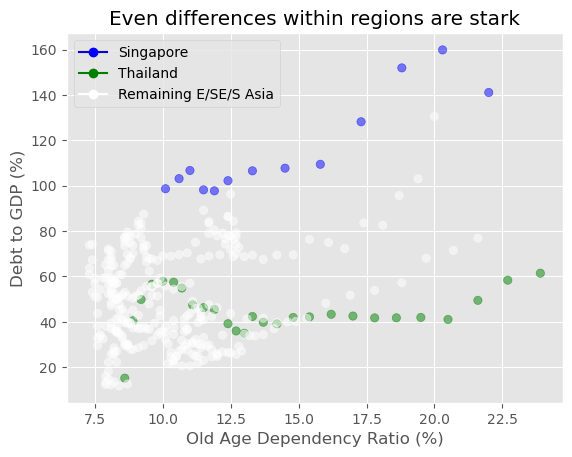

Our analysis considers a much larger set of countries beyond the OECD, which we bucket into region-specific models based upon ISO’s ‘Developing countries’ lists. This is because demographic dynamics differ massively across the globe – comparing countries like-for-like fails to capture these differences and feeds through into incoherent forecasts.

Going one step further, for countries where the data is rich enough, we also build individual country models to help isolate the effect of dependency. There are clear differences even within regions themselves which we want to identify.

Welcome to a new Demographics Watch! We will take a deep dive into public debt and how it’s related to birth rates and ageing population. If you want to go even deeper into our numbers, we have set up a Demographics page on our Datahub, where you can play around with the numbers yourself. It’s for Premium users only – but you can try it out for free with a 14-day trial. Demographics Watch – A Public Debt Timebomb In our first Demographics Watch article, we introduced ‘The Problem Index’ – a measure of a country’s ability to deal with an ageing population. Weighing the pull and push forces of growing dependency (an increasing older population relying on its diminishing working age population) and migration (as one potential way to fill this gap), we outlined the countries most vulnerable to a continuation, or worsening of current demographic trends. Unsurprisingly, it didn’t make for comfortable reading anywhere, but the index suggested two major problem regions – Eastern and Southern Europe, and East Asia. We also highlighted that the Problem Index would serve as the groundwork on which we’d build. Today, we want to expand upon the pure demographic trends explored by considering the second order economic impacts captured by the Problem Index – namely, an ageing population’s impact on a country’s public debt. Before we delve into the forecasts and data itself, a brief 101. The theory itself is relatively straightforward: ageing populations – people living longer […]

0 Comments